Wanna hear something reassuring? Every software development team has problems getting their stuff into production. There, I said it. Now you can take a big sigh of relief, feel better about the absolute mess your team is in, and close the browser tab. Or read on and learn about a tool that can help you tackle these problems.

When it comes to getting software from your grimy old Macbook into the hands of your users one thing is a given: there’s always something to improve, no matter where you are on your Continuous Delivery journey. Some struggle to deploy to production more than twice a year. Others can deploy 10 times a day but keep running into flaky end-to-end tests adding friction to their developer experience.

When I was doing consulting at Thoughtworks, I often worked with teams who were unhappy about their development cadence. They didn’t like how often they were able to ship new stuff to real users. Continuous Delivery started becoming a hot topic back then and companies asked us to help them get started or get better with it.

One tool we used a lot back then, a tool I keep using today even after my consulting days are over, is “Path to Production Mapping”. Thoughtworks call it out on their Technology Radar, but unfortunately don’t go into detail what this is all about. I’m here to fix that. I’ll explain how I usually do “Path to Production Mapping” with teams I work with, and how you can do the same.

“Path to Production Mapping” in a Nutshell

When you run a “Path to Production” exercise, you lock a software development team into a room and don’t let them out before they have created a map that answers the following question:

What does it take to get a change from a developer’s computer into the hands of a real user in production?

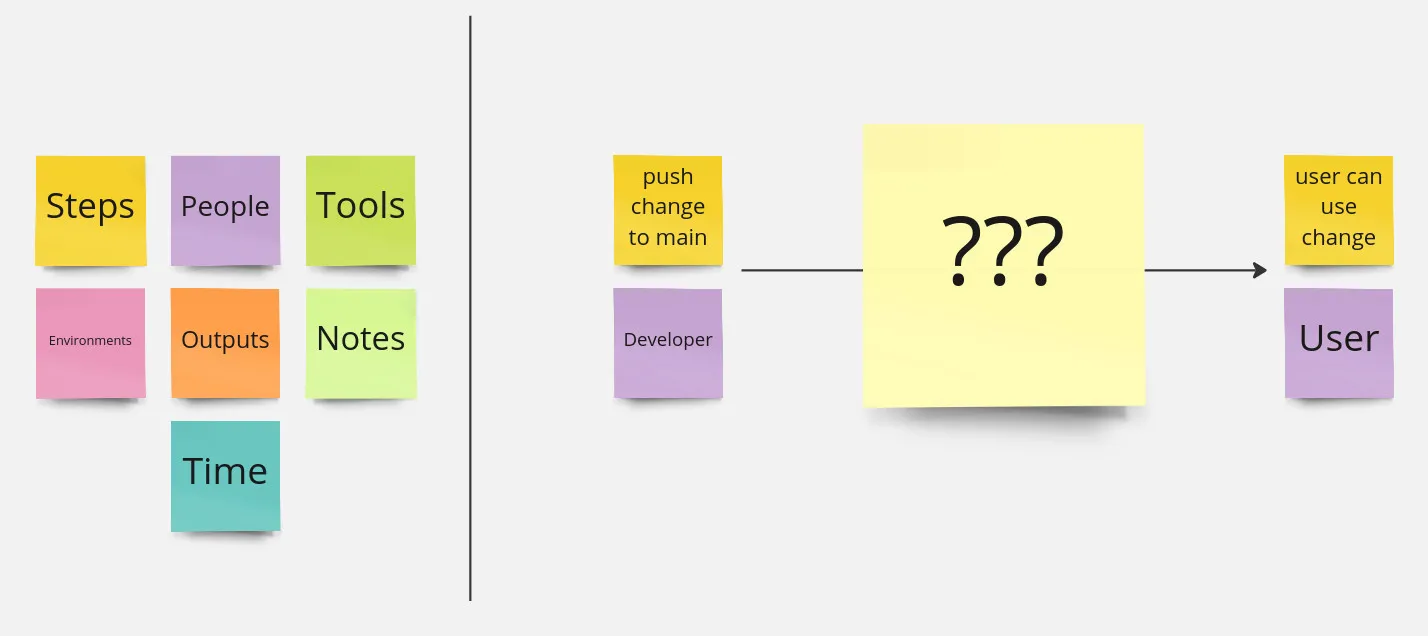

You’re looking to capture the current state, not the desired state (that’ll come later). You start with a blank canvas and define the individual building blocks of your map (the steps, the people involved, the tools used, the time a step takes, etc.). You could start with something like this:

Then you ask people to fill in the big ??? space in the middle. Ask them to write down the sequence of all the manual and automated steps, the people involved, the tools used, and whatever else is important to get your stuff out to production.

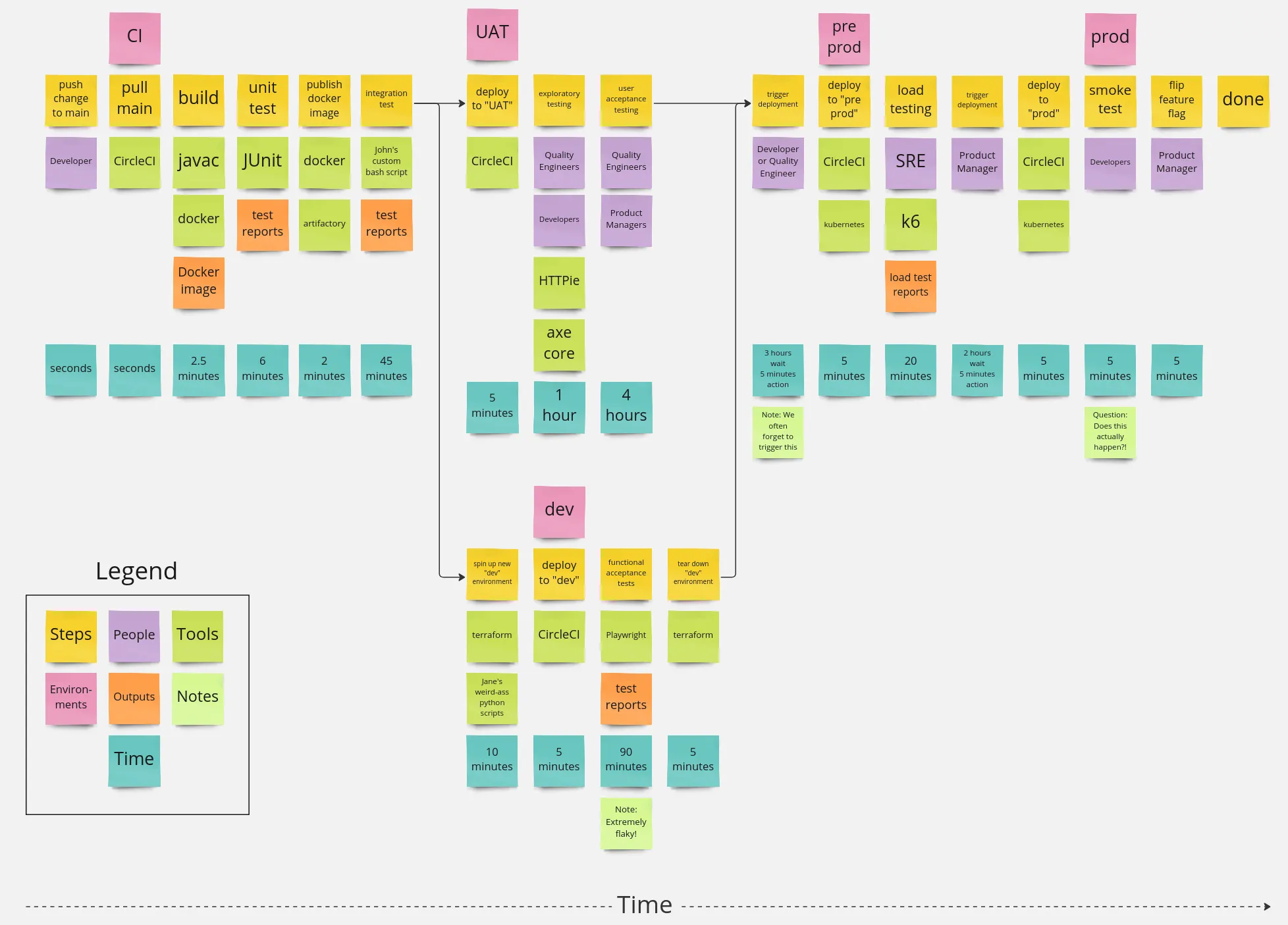

Expect heated discussions. Maybe some yelling. There’ll be the inevitable bike shedding, and finally agreement. After a while you’ll have something like this (click image to see a larger version):

Well done! You finally collectively understand what it takes to ship a change to your users today. Now it’s time to crank up the heat and find ways to improve.

Why You Should Map Your Path to Production

So what? This is just a bunch of colorful sticky notes. What’s the big deal?

You’re a software team. The only software that matters is the one your users can use. Getting your software into the hands of your users efficiently and frequently is important. Continuous Delivery (CD) has emerged as a practice to help you pull that off, and doing it effectively is a proven game changer.

These days a lot of software development teams claim to “do CI/CD” but all they’ve got is an automated build running on every pull request someone puts out there (it’s hard to even classify that as Continuous Integration) and deploying to production involves a lot of manual hand-holding. Other teams are stuck in the dark ages and haven’t taken any steps towards automating build, test, deployment to release software to production reliably and frequently. Even if your team is doing CD properly, your path to production might have grown so complex that you don’t know all the things that happen. Or you secretly loathe the fact that you’ve got to retrigger your pipeline about twice per day because these stupid integration tests are constantly breaking for no good reason. We all struggle with these things one way or another. We’re all on a different part of this journey, and there’s always something to improve about your path to production. And that’s why you want to explicitly map it out.

Running this exercise can help you to:

- get clarity and a shared understanding about your current path to production (you’ll be surprised how different people will have a different understanding of what’s actually going on)

- identify bottlenecks, brittle steps, unnecessary work and things that are completely unknown to the team today

- come up with plans to improve, automate, eliminate, parallelize steps on your path to production

- realize that no single person actually understands the whole process

How to Create Your Path to Production Map

I hope you’re sold on the idea that that mapping your path to production could help you make sense of the mess you’re in. Here are detailed instructions for you if you’re eager to run this exercise with a team.

1. Set Up a Workshop

To create your own Path to Production Map, you set up a workshop where the right people come together to discuss and write down the individual steps of your path to production. This sounds simple but it will be intense.

Plan to take between 2 to 3 hours for this meeting. If you need more time, schedule a follow up meeting, because people’s brains will be fried after this.

2. Invite the Right People

Aim for a diverse set of opinions in this workshop. You want to have people from different disciplines who are involved in getting a change out of the door. You want people with a lot of experience and people who are new to the team. Don’t listen to your rock star developer when he says “we don’t need this meeting, it’s all super simple and I can simply sketch this out in 10 minutes”. That’s bullshit, and you’ll prove it.

Think about inviting the following people. You don’t need to invite literally everyone but try to have a good mix of roles and experience:

- Some of the people who build the software. Software developers, data engineers, designers

- Some of the people who build and maintain the infrastructure your software is built, tested, and run on: Software developers, operations folks, site reliability engineers, platform engineers, “DevOps engineers”, whatever you call them, you know who I’m talking about

- Some of the people who are involved in testing: Quality engineers, software developers, testers, product managers

- Some of the people who decide what gets built and shipped, and when: Product managers, project managers, maybe even someone from marketing

- Maybe even some of the people who take a higher level perspective of what the team is doing: Team leads, engineering managers

Don’t run this workshop with 20 people unless you’re looking for mayhem. 5-9 people seems to be the sweet spot allowing you to have a healthy discussion and avoiding endless debate and bike shedding.

3. Prepare a Canvas

I don’t care whether you do this in person or in a virtual setting. You either take a huge physical space (a whiteboard could be a good start, spreading a huge roll of paper out on a conference table is a good alternative), or you use a collaborative diagramming tool (I’ve used Miro before, others will work just as well).

Bring lots of sticky notes in at least 4 different colors. Bring markers for every participant. If you do this virtually, you don’t need this, of course.

Set up the canvas by showing what each sticky notes’ color is used for (you can swap the colors if you feel frisky)

- Yellow: Steps (automated and manual)

- Blue: People involved

- Green: Tools involved

- Red: Time for each step, and time between steps

You can add more types to the mix if you think it’s worth capturing more: It might be useful to capture comments & questions that come up as part of your discussion, or outputs of certain steps, or environments you run your stuff on. This is your tool, feel free to add what you and your crew thinks is helpful to understand your path to production better.

4. Go Wild!

Once you’ve got everyone in the room and your canvas prepared, explain what you’re going to do: You want to sketch out all the steps it takes right now to get code from a developer’s machine into the hands of your users. You want to capture who is involved in these steps and which tools are used during each step. And finally you want to write down how long each of these steps usually takes, and how much idle time is spent waiting for this step to happen.

Usually there’s going to be some chaos and hesitation in the beginning. People are shy to start, argue about the right level of detail, get lost in meta-discussions. It’s okay to let these happen for a bit but after a few minutes you should encourage them to just get started and write something down to get the ball rolling. This is not an exam, there’s nobody grading what he team comes up with. If you’ve set this workshop for 2 hours, tell them they should be done with the “mapping” part after 1 hour. This will give you some room to extend their time, but it’ll give the team a sense of urgency.

During the mapping exercise, expect that the team will come up with some obvious steps rather quickly, while others are surprisingly controversial and come with a lot of discussion, questions, and back and forth. This is a great time for newer team members to ask questions, for people in non-technical roles to learn more about the technology used, and for the technical folks to better understand what business decisions are driving your development process.

Be mindful about rabbit holes and derailing conversations. Teams often get lost in details that don’t quite matter in the grand scheme of things. If you spot these discussions, make sure to help the team get out of it by breaking it up, putting down a sticky note with the open question so that you can revisit later, and move on.

5. Analyse the Map

Once the path to production map is done, you should take a deep breath and a short break. The next step is to analyze the map the team has created. You could either do this as part of the one session you planned or schedule a follow up. Be mindful of the energy levels in the room, creating the map can be exhausting and people might be fried by now.

When it comes to analyzing the path to production map, to take a look at all of the steps you outlined and the time each step takes. Discuss where you can find room for improvement. Highlight the pain points and write down first ideas that come up to tackle these problems.

Some things to think about:

- Which steps take a lot of time today? Could you cut that time down by using better automation or changing your approach completely?

- Where do you have handovers that lead to a lot of waiting time?

- Are there manual steps you could automate?

- Are there steps that don’t provide a lot of value that you could eliminate or cut back on? Be rigorous. Over time a lot of cruft creeps as it’s always easier to add something than to remove something. Often you learn over time that something that sounded like a good idea a year ago isn’t actually pulling its own weight.

- Are there steps you could parallelize instead of running them in sequence?

- Are there steps you could take off the “hot path”? Could you get your changes out to production without waiting for the result of certain steps? Feature flags can help to decouple deployments from releases, which can be useful to buy you much more safety and flexibility in these regards.

- Are there things to streamline and simplify? Do you, for example, have three different deployment methods for your various environments that you could unify?

- Are the steps in the right order and optimize for fast feedback? Watch out for long running tasks that run earlier and push out quick verification steps to a later point in time and see if that’s worth fixing. Usually, you’d want your unit tests to run before your integration tests, for example, since they’ll give you valuable feedback much quicker.

- Which steps are currently unreliable and could be made more resilient? Do you have certain deployments that often fail? A flaky test suite? Think about making these more reliable, replacing them with a different approach that is more reliable, or getting rid of them altogether.

As you discuss these things, write down the pain points and possible solutions. Let the conversation flow, there will probably be a lot of ideas, some good, some bad. Capture them all for now. Think about giving the team an opportunity to add more ideas even after the workshop’s done.

6. Follow Up

After this exercise you will have a few things:

- A visual map showing how you get your software into the hands of your users today

- A shared understanding and agreement on your path to production

- A lot of ideas where you could improve your current process

Don’t let this go to waste. The Path to Production Map is great for onboarding new team members. It’s a great living document you could change as your path to production changes. Think about making this visible to your team in an easy way.

More importantly, the list of improvements is something very actionable that could help you turn your current process from something that everyone resents into something that allows you to experiment, innovate, and ship stuff reliably and frequently. Make sure to prioritize the work accordingly.

Summary

If you and your team (or a team you know and care about) are frustrated with how you ship your software to production, it’s tempting to quickly jump to conclusions, flail around aimlessly and try to improve something, anything by writing yet another script or including yet another tool. Mapping out your Path to Production can be a smarter approach that allows you to take a step back, see the bigger picture first, create shared understanding and have structured discussions about what’s painful at the moment and why everything sucks so much.

Shipping software to production is more of a social problem than a lot of us developers are ready to admit. Treat it accordingly. Gather everyone in a room, map out your path to production, analyze where your problems truly are and discuss the big ideas to improve your situation together.

I hope this exercise helps you as much as it has helped me in the past. If you’ve got questions, doubts, feedback, or comments, feel free to send them my way. All my contact data is crammed into the footer of this page.

Further Reading

- Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit by Mary Poppendieck and Tom Poppendieck for more details about value stream mapping (see Chapter 1).

- Continuous Delivery: Reliable Software Releases through Build, Test, and Deployment Automation by David Farley and Jez Humble for a lot of great advice around setting up a deployment pipeline for your automated path to production and for a fundamental introduction to Continuous Delivery